Desire, irresistibility and the intoxication of a seductive idea

Many brands craft a desirable product. Few create a powerful enough idea to change culture itself. Brittany Golob analyses the impact brands have had on behaviour

Imagine a world without engagement rings, without Santa Claus, without bras. A world where women never chose to shave under their arms, where chocolate is not good luck, where emojis and Black Friday shopping don’t exist. Imagine a world without soap operas or credit ratings or weekends.

Separately, they might not make much of a difference, but together, cultural behaviour in countless places around the world would look starkly different. Many companies have released products that have changed lives or changed categories – some have even invented new categories. But there are few that have truly embedded those concepts into culture so that the behaviour becomes removed from the brand.

Perhaps the most well-known instance of a brand influencing culture is Coca-Cola. Its fizzy drinks are sold everywhere except Cuba and North Korea, but one of its early marketing campaigns has made a different impact.

Coca-Cola struck a chord with its 1931 Christmas campaign, which saw artist Haddon Sundblom reinvent Santa Claus. The red-coated, white-bearded patron saint of Christmas was born and graced subsequent campaigns until 1964. Ted Ryan, director of heritage communications at Coca-Cola, says in a film, “I think now when people envision Santa Claus, they envision the Coca-Cola Santa Claus. Many of them don’t even know the origin; the fact that Haddon Sundblom painted this perfect vision of Santa Claus.”

It’s a bit of history of which Coca-Cola is clearly proud, having supported an exhibition of Sundblom’s work in 2012, but it has also seeped into culture and become an image separate from Coca-Cola itself, transcending brand and product. The beauty of the Coca-Cola Claus is that it wasn’t intended to change the world. It began as simply, a nice image and a relevant advert.

Crafting an image or an idea that is intoxicating, powerful and utterly unique is a rare thing. And often the intentions are not to revolutionise the world, but to make a simple change. However, those changes can be impactful.

Dan Claxton, creative director at London-based agency BD Network, says, “I’m not sure how many of the brands that have had an impact on culture ever set out to do so. In reality, it is a by-product of having a great brand and product and selling it in the right way to the right people and answering a genuine need.”

Those that have made a lasting impact on culture or behaviour typically have done so as a result of either a clever use of semiotics, a serendipity in timing or innovation or the spiralling effect of product-based intentions.

Semiotics, the use and understanding of symbols as a means of communication, is something consistently exploited by brands to achieve cut-through, engage with culture and improve memorability. Cato Hunt, director at Space Doctors, an agency that focuses on semiotics as a means of connecting brands to culture, says “It’s about owning a cultural space and about a brand reading culture and trying to understand, ‘How do I make my mark? How do I change culture positively?’”

The De Beers Group put semiotics to use – and it has made the difference between massive, global success and relegation to the lower ranks of luxury branding. In the 1920s, when diamonds were first brought from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe and beyond, De Beers sought to regulate the diamond market to increase the perception of diamonds as a precious stone. But, it wasn’t until an advertising campaign at the height of the Great Depression that diamonds become something to own – forever.

In 1938, De Beers worked with ad agency N.W. Ayer on a campaign turning the diamond, and particularly the diamond ring, into a sentimental symbol for eternal love. The tagline ‘A diamond is forever’ was born. This correlation was needed to encourage young men to purchase diamond rings for their fiancés and, in turn, to encourage young women to desire a diamond ring from their beloved. The campaign influenced celebrities, fashion designers and magazines to portray the diamond as a symbol of love and romance.

The slogan was reintroduced in 2016 to the De Beers Forevermark brand. But diamond consumption is changing, a fact De Beers hopes to capitalise on with the renewed energy behind the ‘A diamond is forever’ branding. Bruce Cleaver, CEO, De Beers Group, said in a release, “As diamonds are among the most powerfully symbolic purchases, as they lend themselves to individual design, and as they are effectively a hybrid of product and experience, the new trends present a major opportunity to build on the existing base of demand.” Yet, he notes that diamonds are still most commonly given as symbols of love. That initial correlation of the diamond with romance still stands 79 years after its inception.

Rebecca Robins, global director at Interbrand and co-author of the book Meta-luxury, says, “De Beers elevated the value of the diamond to a timeless investment and linked it intrinsically to one of the most emotive of moments in our lives. They built an ecosystem, from influencing how people experienced the brand, to introducing the four Cs (colour, cut, clarity, carat) to their ads, to setting a standard in expectation – ‘Isn’t two months’ salary a small price to pay for something that lasts forever?’ – all of which drove authenticity and relevance and, ultimately, customer choice.”

She adds, “‘A diamond is forever’ is also proof positive of the value of something that’s often overlooked by brands. The value of words and the language they use. Words can make a difference. And the right words can make a definitive difference to the bottom line.”

Ironically, another organisation that has capitalised on semiotics is SmileyWorld, which represents the replacement of words with symbols. The company owns the trademark on the humble smiley face icon, and its fellow emojis, licenses the use of its products in 100 countries and earns £265m annually on retail sales. The so-called ‘happiness revolution’ the brand began in the 1950s has created a viable business model, but has also filtered so deeply and intrinsically into culture that emojis are available on virtually every smartphone. With appearances at the London Olympics opening ceremonies, in 2009’s Watchmen film and the – ill-fated – 2017 Emoji Movie, the smiley is a true cultural icon. And it is inherently linked to happiness; a success in semiotics.

But often, brands that have influenced culture and behaviour have done so not through a calculated intention, merely as a happy accident that they then were able to capitalise on. Santa Claus is a prime example. Coca-Cola still features a red-clad, rosy-cheeked St Nick on its Christmas packaging year after year.

Kit Kat is another. In Japanese, there is a serendipitous correlation between Kit Kat’s pronunciation in Japan – ‘kitto katto’ – and ‘kitto katsu,’ meaning ‘sure to win.’ This stroke of literal and figurative luck has helped Kit Kat become a market leader in Japan. The Nestlé-owned brand is the number one chocolate in Japan and sells 4m products daily. Japan is also one of Kit Kat’s most innovative markets with 30 current varieties in the marketplace, regional specialties and new flavours debuting each season. The country is also home to the Chocolatory, a unique chain of patisserie stores and a premium range of Kit Kat.

Beyond this success, the Telegraph reported in 2005 that sales of Kit Kats increase during exam and university acceptance periods as students receive the good luck symbols from friends and family. Kit Kat has transcended category. In Japan, it is not simply a nice chocolate bar, it is a cultural touchpoint. Hunt says brands that impact culture in such a way have, “Made that connection and changed what you do to celebrate the moment.”

Good luck, indeed.

For some brands, though, changing behaviour is more than the result of good timing and good luck. For brands like Gillette, P&G, Wonderbra and now-defunct American department store Lazarus, good intentions for their own brands created huge shifts in culture that transcend the product and the brand itself. They have created truly intoxicating ideas.

One of those legends is Henry Ford, who is credited with giving his employees the first two-day weekend. Many thanks, Henry.

In that vein, Fred Lazarus can be credited with the origination of the modern Thanksgiving holiday in the US. Though it has been celebrated since 1863, it was Lazarus and President Franklin Roosevelt who, in 1939, set it permanently on the fourth Thursday in November, thereby giving Lazarus, and his fellow retailers, an extra week of Christmas sales – which begin, notoriously, on the day after Thanksgiving, or Black Friday. Initially driven by a sales decision, Americans now take their holidays seriously – Thanksgiving for turkey and Black Friday for top sales. Many thanks, Fred.

“Brands are related to culture. A powerful lens through which to look at brands is how much we would miss them if we woke up tomorrow and the business had disappeared”

“A lot of companies were buying airtime and supporting shows. P&G was very different because we wanted to go ahead and own the content, to be in control of the message”

One of the most impactful stories is that of the soap opera. Now an omnipresent feature of modern television, it is not well known that the popular dramas are named for the soap companies that used to sponsor their radio predecessors. Though an unbranded phenomenon, it was P&G who prompted this trend, and P&G who perpetuated it until 2010 through its in-house production arm, Procter & Gamble Productions.

“Radio was a brand new technology, much like the internet was at the eve of the 21st century,” Greg McCoy, P&G’s senior archivist, says. Companies were trying to capitalise on the advent of radio.

It started innocuously. P&G offered cooking tips in the 1920s through its then-leading brand Crisco. The shows consisted of a 15 minute period in which a host would read out a recipe or offer advice on cooking with Crisco. This early example of content marketing would set the stage for a cultural revolution in entertainment.

Through market research, P&G found that its key audience of women “really didn’t have time to sit there and jot down recipes,” says McCoy. “They were busy, tending home, tending children, busy with their lives. What they wanted to do if they got 15 minute window in a hectic day was not write anything down; they didn’t want to read anything instructional. They wanted to be entertained.” And so, P&G took up the challenge of entertaining them.

Determining that little content in existence suited P&G’s brand values or intentions for communicating through radio, it set up its own content shop and became an entertainment company. “It was very uncommon. A lot of companies were buying airtime and supporting shows. P&G was very different because of the fact that we wanted to go ahead and own the content, because we wanted to be in control of what those messages were,” McCoy says.

Creating dramas and comedies in the production studio, the new soap operas allowed P&G brands, like Oxydol, to sponsor the programmes and get their message across against content that made sense for the brand. By the time the moniker ‘soap operas’ first came into use in the 1930s, they had taken on a life of their own. Though P&G continued to own shows like Guiding Light or As the World Turns until the 2000s, soap operas had become appropriated by culture, leaving their original relationship with soap producers to the annals of history. Now, P&G has turned to digital channels and to unleash a new form of branded content on the masses – one of whom is Old Spice’s popular ‘The man your man could smell like.’

In hygiene and fashion, culture-changing brands are rife. One of whom, Wonderbra, crafted the first modern brassiere by abbreviating the then-omnipresent corset shape into its ‘Petal Burst’ shape with pointed cups that ushered in a new world of freedom from corsets.

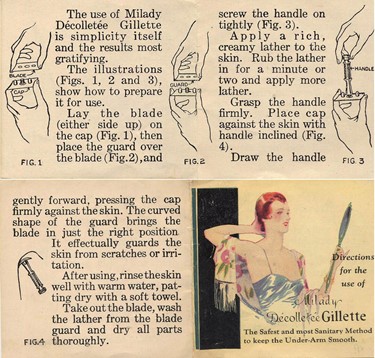

Gillette, a P&G brand, is also responsible for a shift in feminine cultural behaviour. Its ‘Great underarm campaign’ of 1915 was the first to introduce underarm shaving to women. Its ads were educational, rather than promotional, and instructed women how to use Gillette safety razors to enhance their stylishness.

Today, Gillette is still tying its brand to cultural changes. Its popular Dollar Shaving Club – now owned by Unilever – led the shift in attitudes toward male shaving. Hunt says, “One of the challenges that a brand like Gillette has had is that, over time, it has felt quite gendered. And I think people don’t respond to being told what they should or shouldn’t look like.” Space Doctors has worked with Gillette recently to shift the concept of masculinity to embrace a more open, less gendered image. Fellow Space Doctors director Steve Seth adds, “Visions of masculine performance and achievement are very important in identity categories like shaving and skincare, and also alcoholic drinks or cars. How you showcase and depict achievement is really important and underlies how successful you are in the marketplace.”

Perceptions and peer recommendations are becoming more important. Matt Haig, author of Brand Failures, writes, “Image is now everything. Consumers make buying decisions based around the perception of the brand rather than the reality of the product. While this means brands can become more valuable than their physical assets, it also means they can lose this value overnight. After all, perception is a fragile thing.”

That shift may make it more challenging for brands to affect change in culture. But it hasn’t stopped them trying. Robins points to brands like Viagra and Prozac which have opened the discussion about medical issues and changed people’s attitudes and behaviours toward them. She says, “Brands are related to culture. A powerful lens through which to look at brands is how much we would miss them if we woke up tomorrow and the business had disappeared. Brands that hold that magical place do so because they’ve found their way into both our hearts and minds. They’ve created a magnetic confluence of desire and demand.”

To succeed financially, brands have to tap into culture, but to create the irresistible, the intoxicating, the powerful ideas, brands have to shape culture; and that is something that makes a difference.